Way too much information on the Florfox

A detailed look at how I developed the Florfox, and the rationale for it's existance.

CREATURES & RACESWORLD BUILDINGBEHIND THE VEIL

7/6/20254 min read

I took an advance horticulture course a few years ago, and while reviewing my notes, I had a thought about a creature who could use photosynthesis...This led me down the rabbit hole again, and thus was the Florfox created. When creating things for the world, I would much rather know how they work / why they work, and have a solid reason behind things. One thing I try to ensure is that everything that makes it into the world (as much as possible) - and certainly things that make it into the novels, have some sort of reasonable foundation.

So, while there is some basic information about the Florfox on the Creatures page, for those of you who are interested in the process of creation - or just want to know why I think something like this could/should/would exist in a fantasy world, I present my notes on the Florfox:

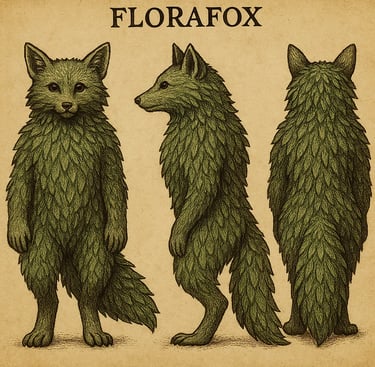

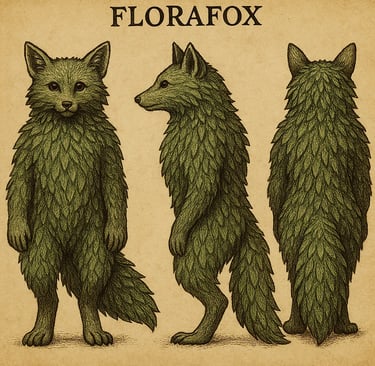

A curious blending of mammalian and botanical traits, the Florfox appears—at first glance—to be a small fox or wolf, perhaps a woodland subspecies adapted for camouflage. Closer observation, however, reveals a creature more remarkable: one whose body has embraced symbiosis with sunlight itself.

Covered in flat, blade-like hairs that shimmer in shades of green, the Florfox’s coat is not simply pigment—but structure. Each filament functions analogously to a foliar blade. It contains a waxy cuticle to reduce desiccation, stomata-like pores for gaseous exchange, and internal cells laced with chlorophyll. Unlike fur, these hairs are leaf-like in cross-section—broad and flat—and flexibly articulate at the root, allowing the Florfox to adjust the angle of its coat toward sunlight. In full sun, it will spread these filaments slightly outward—forming a kind of micro-canopy that maximizes exposure.

The hairs serve as the primary photosynthetic surface for the Florfox. However, the animal itself is not solely responsible for this energy conversion. Its outer skin layers house a mutualistic photosynthetic microorganism, similar in behavior to coral-dwelling algae (but genetically distinct). These symbiotes occupy shallow dermal pockets at the base of the fur shafts and within upper epidermal channels. Together, fur and symbiote form a complete solar-capture system.

The photosynthetic process is relatively efficient, thanks to an unusual adaptation: the Florfox’s circulatory system actively delivers CO₂ and water to dermal capillaries, aiding the symbiotes. In turn, the symbiotes produce both glucose and oxygen, which are absorbed directly into the bloodstream.

Unlike typical mammals, the Florfox’s blood chemistry has evolved to accommodate this sugar influx. Its blood contains a specialized compound known as hemoglucin—a modified carrier protein analogous to hemoglobin. Hemoglucin is capable of binding both oxygen and glucose molecules, allowing the Florfox to transport sugar and air simultaneously via the same vascular channels. Importantly, the molecular structure of hemoglucin is resistant to glycation, the process by which sugars damage tissue proteins in most organisms. This immunity permits the Florfox to maintain exceptionally high circulating sugar levels without organ damage.

In times of light surplus, the Florfox stores excess glucose in a specialized organ called the Sccydden. Oblong, warm, and positioned behind the stomach, the Sccydden is the primary energy reserve organ. Within it reside cellular structures called photoroplasts, unique to the Florfox genus. These organelles appear to be a hybrid of chloroplasts and mitochondria—capable not only of photosynthesis but of processing the resulting sugars directly into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In effect, photoroplasts allow the Florfox to bypass glycolysis, generating usable energy in the form of ATP from light-derived sugars stored in the Sccydden.

Photoroplasts are capable of switching between active solar conversion and stored-energy processing, allowing them to operate both during the day and into the night, drawing on the internal sugar reserves when sunlight is absent.

Respiration is primarily nocturnal. During daylight hours, the Florfox focuses on light absorption and photosynthesis. At night, it metabolizes stored sugars and oxygen—either gathered during the day or absorbed through traditional respiration—to fuel activity. This dual system enables the Florfox to operate for long periods without feeding, so long as sunlight is ample.

Still, the Florfox is not entirely autotrophic. It supplements its energy intake with roots and tubers, primarily to source minerals and trace nutrients not available through photosynthesis or microbial synthesis. Its diet is simple, but its digestion tract is flexible—adapted to extract nutrients efficiently from starchy material.

The leaf-fur changes with the seasons. During the warm months, the coat is vibrant green. In autumn, the chlorophyll within each hair degrades, giving way to yellow, orange, red, and brown carotenoids and flavonoids—much like deciduous leaves. This serves a dual function: camouflage and photonic insulation. Before winter sets in, the creature molts the old coat, and a tighter, less photosynthetic layer emerges beneath to preserve warmth. A new photosynthetic coat emerges again in spring.

Socially, the Florfox is a communal animal, often living in small herds of 20–30 individuals. These groups groom each other regularly—likely to maintain both fur hygiene and the health of the photosynthetic symbiotes. Grooming behaviors focus particularly around the shoulders, back, and tail base, where sun-absorption is highest. Herds are loosely territorial, rarely aggressive, and rely on coordinated movement to avoid predators. Their primary defense is speed and an uncanny ability to blend into the underbrush when stationary.

The average lifespan is 10 to 13 years, though individuals in captivity or protected habitats may live slightly longer.

Though generally peaceful and well-integrated into their ecosystem, the Florfox is sometimes hunted—not for its meat (which is mild and slightly sweet), but for its blood. The sugar-rich blood, when fermented, produces a potent, reddish beverage called Sanguintin. Said to warm the chest and “lighten the mind,” Sanguintin is prized in cold regions (it is a favorite of the Goebs) and ceremonial feasts of the Quem. The fermentation process converts the blood’s natural sugars into alcohol, while retaining trace proteins that give the drink a slightly umami backbone. It is thick, nearly syrup-like, and considered a delicacy.

Florfox populations are currently stable but may be vulnerable to overharvesting, particularly in regions where Sanguintin has ritual or economic significance. It is "protected" by the Alfay - and hunting or havesting them in the Empire is a crime.

Summary of Key Adaptations:

Fur Structure: Leaflike filaments with cuticle, stomata-like pores, and chlorophyll-bearing cells.

Symbiosis: Photosynthetic microorganisms integrated into dermal tissues; produce glucose and oxygen.

Circulatory Adaptation: Hemoglucin carrier protein binds both oxygen and glucose; resistant to glycation.

Energy Storage: The Sccydden stores sugars; contains photoroplasts that generate ATP directly.

Respiration: Daytime photosynthesis; nighttime aerobic metabolism of stored sugars.

Diet: Primarily photosynthetic with supplemental mineral intake via roots/tubers.

Seasonal Coat Shift: Green during warm seasons, autumnal hues before molting, with winter coat regrowth.

Behavior: Communal grooming, sun-basking, herd movement. Lifespan 10–13 years.

Cultural Significance: Hunted for its sugar-rich blood; basis for fermented drink Sanguintin.